(Warning: this post contains references to suicide, violence, and torture)

“I consider such a venture entirely beyond comprehension.” These were the words, translated to English, of course, of Ōkubo Toshimichi, one of the first of the “genrō.” An advisor to the Meiji emperor, Ōkubo was talking about the 1873 proposal to conquer Korea.

Other members of the genrō group, including Saigō Takamori and Itagaki Taisuke wanted to invade. Saigō believed that it would provide an outlet for the “restless” samurai. They were losing their rank, their lands, and their privileges as a part of the the Meiji reforms. Saigō seemed to hope to make up for this. Ōkubo could not countenance their ideas. During the debate he laid out his reasons why.

He concluded with the idea that an invasion, “completely disregards the safety of our nation and ignores the interests of the people. It will be an incident occasioned by the whim of individuals without any serious evaluation of eventualities or implications.” To invade was an emotional decision. It was not logical. To colonize Korea was bad for Japan.

The argument itself was well-organized and enumerated. It was not emotional, but full of facts and predictions based upon those facts. They include the massive cost of a military buildup and an invasion. Japan did not have enough revenue to both modernize and fight to a foreign war of conquest. To do both required foreign loans. Japan, he noted, did not yet have a plan to repay the loans already taken. Further loans would lead Japan to weakness. That could result in its being colonized by a Western nation.

All these were solid reasons to avoid war, backed by real facts on the ground. He finishes his summary, though, by saying:

Even if the campaign [to conquer Korea] makes a favorable start, it is unlikely that the gains made will ever pay for the losses incurred. What will happen should the campaign drag on for months and years? Suppose total victory is gained, the entire country occupied, and the Koreans permitted to sue for peace and to indemnify us. Still, for many years, we shall have to man garrisons to defend vital areas and to prevent their breach of the treaty terms. When the entire country is occupied it is certain that there will be many discontented people who will cause disturbances everywhere, making it well-night impossible for us to hold the country. In considering the cost of the campaign, and of occupation and defense of Korea, it is unlekly that it could be met by the products of the entire country of Korea. Then there is Russia, and there is China.

Any reader familiar with Japan’s occupation of Korea is struck by the power of Ōkubo’s foresight. Every one of the disadvantages he enumerated did, in fact, come to pass.

It is possible to argue that the campaign did not drag on for years. But that is only if we think of “the campaign” very narrowly as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 alone. In fact, the battle to control Korea lasted from 1904 to 1945, almost exactly 40 years. That was forty years of military expenditure. It was forty years of administrative and organizational challenges and costs. Worse, it was forty years of mistreatment of Koreans and “discontent” among them.

Japan did have to maintain garrisons to defend vital areas from 1905 to 1945. That military occupation left Koreans battered, both as individuals, and as a society. It created the very discontent it was meant to protect the vital areas from. It poisoned Japanese-Korean relations for the foreseeable future. Even today, the bitterness and anger in Korea towards Japanese is constant and just below the surface.

I was noticed this when watching Netflix’s recent release of the Korean drama Hymn of Death. This is the story of Yun Sim-deok. She was a Korean who went to Japan to study opera. While there she recorded Korea’s first popular record - “Hymn of Death." This song was a suicide note to the world as she and her married lover left this world rather than be separated. The drama is beautiful and sad, as one might expect. What I did not expect, despite having studied the Japanese empire, was the way that Japanese were depicted. In the drama they are always shoving guns in the faces of Koreans. They are always insulting Koreans. They are always looking down on Koreans in a racist way.

This is the Korean memory of Japanese. They are seen as angry people who yell and spit in your face during what should be a normal conversation. Their image is of people who resort to violence at the drop of a hat. To Koreans, Japanese do not accept a compromise solution with a Korean - any Korean - for any reason.

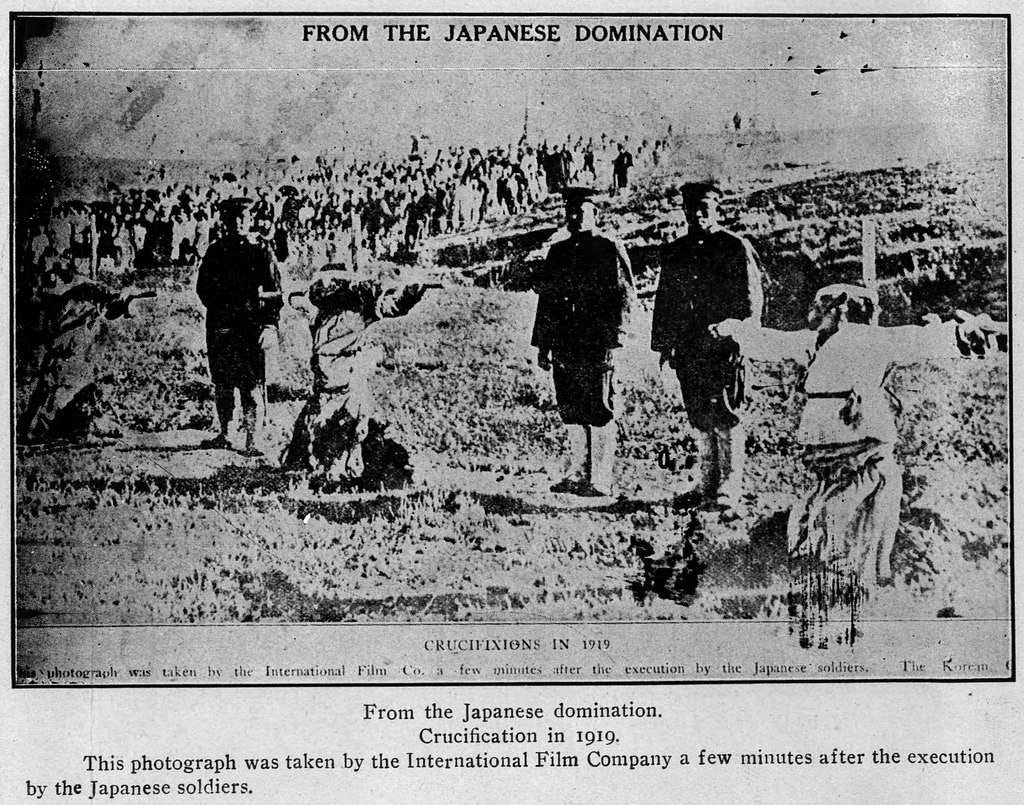

The memories of occupation are still fresh in the minds of Koreans. This is no surprise. It appears that Ōkubo was right. There were “many discontented people” who “caused disturbances everywhere.” To "hold the country," it became the policy of the Japanese colonial government to use threats, violence, torture, and fear.

As Ōkubo predicted, Japan tried to export its way out of the costs of ruling Korea. Koreans were kept in poverty. This was not just to repress their ability to resist, but because low wages and long working hours were the way in which costs could be kept down. Profits in Japan had to be high. Those profits never did pay enough to balance the cost of empire. As Ōkubo predicted, both groups lost. Koreans lost their dignity, their livelihood, their physical safety, and their lives. Japanese lost their security, their modernity, their soldiers, and their national wealth. Neither gained from the exercise.

Last, Ōkubo predicted that Russia and China might take advantage of the fact that occupying Korea weakened Japan. “[Who] can say,” he noted in his summary, “that the governments of these two countries will not plot and take advantage of the opportunity to bring about a sudden and unexpected calamity?”

Both, of course, did so. Ōkubo’s argument stayed the hand of the invasion faction, but did not prevent Japan from working in other ways to subjugate Korea. In my last post, I discussed the Treaty of Kanghwa, which created a treaty port system in Korea similar to the one the U.S. had imposed upon Japan. This did not end the debate, however, and China and Russia certainly played their parts in helping Japan’s hotter heads to prevail in the long run.

China in 1894 broke its agreement with Japan to give notice that it was sending soldiers back in to Korea. This led to the First Sino-Japanese War. Japan won that war. However, in 1895 the “Triple Intervention” forced Japan to give control of Korea and Manchuria to Russia. Russia became the key barrier to Japanese “protection” of the “independence” faction of the Korean government. That lead directly to the costly Russo-Japanese War. Again, Japan won. But as Ōkubo predicted, that victory was pyrrhic. It was the beginning of Japan's troubles in occupying a Korea that did not want it there.

Ōkubo was not prescient. He did not have his head in a crystal ball in his back room somewhere. He was no Nostradamus. Instead, he was an avid student of international and national politics, a realist, and knowledgeable about history and the world. He looked at the facts, and he recognized no advantage to Japan in making Korea a part of its empire. His argument came down to one key point. It might make Japan feel victorious to occupy Korea, but a decision for war based on the feels is dangerous, costly, counter to the goals of Japan. Based on the facts, it was a bad idea. Here was his break with Saigō, his long time friend: Saigō’s support for war, he thought, was emotional. Logic dictated a different approach.

I can’t help thinking he was right. The effects that Ōkubo predicted bore out his argument. Japan did pay dearly from 1905 to 1945. These effects eventually led to the destruction of the imperial state, and millions of lives, both outside and inside of Japan, during World War II. All this for an emotionally-driven, nationalist, exceptionalist, decision for war in 1904.

Beasley, W. G. Japanese Imperialism 1894 - 1945. 15. print. Clarendon Paperbacks. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010.

———. The Rise of Modern Japan. 2. ed. New York: St. Martin’s Pr, 1995.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Third international edition. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Oda, Yasunori. Nihon kindaishi no tanken (Exploration of Modern Japanese History). 1st ed. 1 vols. Kyoto: Sekaishiso Seminar, 1993.

Sims, R. L. Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Tsunoda, Ryusaku, William Theodore De Bary, and Donald Keene, eds. “Sources of Japanese Tradition. Vol. 2,” Text ed. in 2 vol., [Nachdr.]. Introduction to Oriental Civilizations. New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2000.

Thank you for another interesting and eye-opening article. I already knew the facts but not all the details, including Okubo Toshimichi's opinion.

I actually just came across this recently myself. I knew Okubo opposed the idea of invading Korea, but the fact that there was such division among the Genro, and that Okubo carried the day on that occasion were new to me as well. It's not Taisho, though! Need to get back to my roots!