When I think about imperialism in general, I often recall a scene in one of the first modern horror films, 1922's Nosferatu. The great shadow of a hand extends grasping over a city. Imperialism feels the same to me, both as an image, and as the deep seated feeling of horror that image brings to mind. Despite the horror, however, History requires that we look at the past in its entirety. It's time to talk about Japanese imperialism.

Taishō would not have been Taishō without the rising spectre of the Japanese Empire. Eventually Japanese propaganda cloaked the empire in anti-Western-imperialist rhetoric. But Japanese calls of "Asia for the Asians" were hollow and self-serving. They were also not unique for their time. That does not excuse the fact that Japan's empire was an ugly, grasping claw expanding over Asia in the first half of the twentieth century.

To understand the empire's beginnings, we have to jump backward from Taishō to Meiji. This will allow us to see the process by which Japan created its colonial reach. One thing that is always striking is how short the reach was. Japan's empire did not grasp colonies in far reaches of the globe. Rather, Japan built an empire in its own backyard, starting with Okinawa, Taiwan, and Korea.

In 1868, the Meiji Period began in part because of a rebellion of various samurai domains. They were angry that the Tokugawa Shōguns acceded to American demands. Emperor Kōmei had already issued a dictum ordering the expulsion of the American barbarians and the preservation of Japan as a sacred place. That did not happen. In 1854 the Shōgunate signed the Convention of Kanagawa, opening relations with the United States. In 1858 the U.S. and Japan signed the Harris Treaty. This formally ended Japan's isolation policies. It also opened various ports to U.S. Trade. Last, it established extraterritoriality for U.S. citizens in Japan. Again in 1858, Japan signed the Ansei Treaties with other Western powers. They extended all trade advantages granted to the United States to other "most favored nations." Some samurai domains were angry that the Shōgunate had ignored the will of the emperor. They were also looking for a way to get out from under the Shōgun's power. Those domains, Satsuma, Chōshu, and Tosa, rebelled. When they won, they forced the last of the Tokugawa Shōguns to resign. They then promptly realized why the Shōgunate had capitulated. U.S. naval power was too much to resist. So they also honored the treaties signed by the Tokugawa Shōgun. In 1868 the emperor Meiji was "restored" to a power that emperors had not exercised since at least the Genpei War of 1180-1185. This was the beginning of the Meiji Period.

The key issue here is the treaties mentioned above. They were based on the example of the treaties Great Britain signed with Qing-Dynasty China after the Opium War (1832-36) and the Arrow War (1854-64). Those treaties granted unfair trade advantages to Great Britain. China was to allow British traders to enter and establish themselves for trade at specific trading ports. China was not allowed to control imports or exports within its borders. The British were allowed to levy tariffs and control Chinese exports to Great Britain. British citizens in China had the right to be treated according to the law of Great Britain. This was known as extraterritoriality. There were other provisions, as well. The important point is that the treaties were not reciprocal. They were unequal. Worse, China had to trade with other Western powers the same way as it did Great Britain.

This unequal treaty system was part of a new phase of imperialism. We can think of it as imperialism on a budget. It focused on maximizing profits while minimizing the costs of direct rule. The United States applied this model to Japan using the treaties signed in 1854 and 1858. For Japan, finding ways to convince the United States and other Western powers to revise those treaties was a major driver of industrialization and modernization after 1868. Most Japanese, whether they were aware of imperial dictates or not, in 1868 most likely felt the same way as Emperor Kōmei had. They did not excitedly embrace "modernization" but felt compelled to modernize their industry, infrastructure, and military to prevent the colonization of Japan.

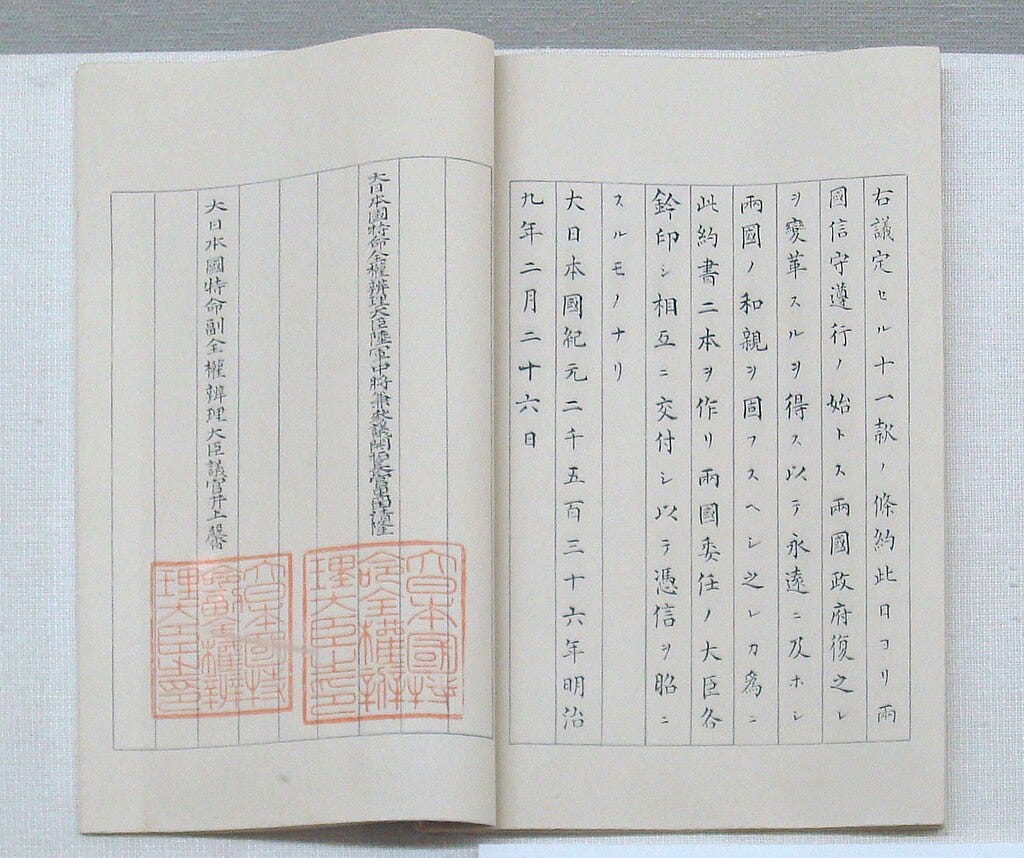

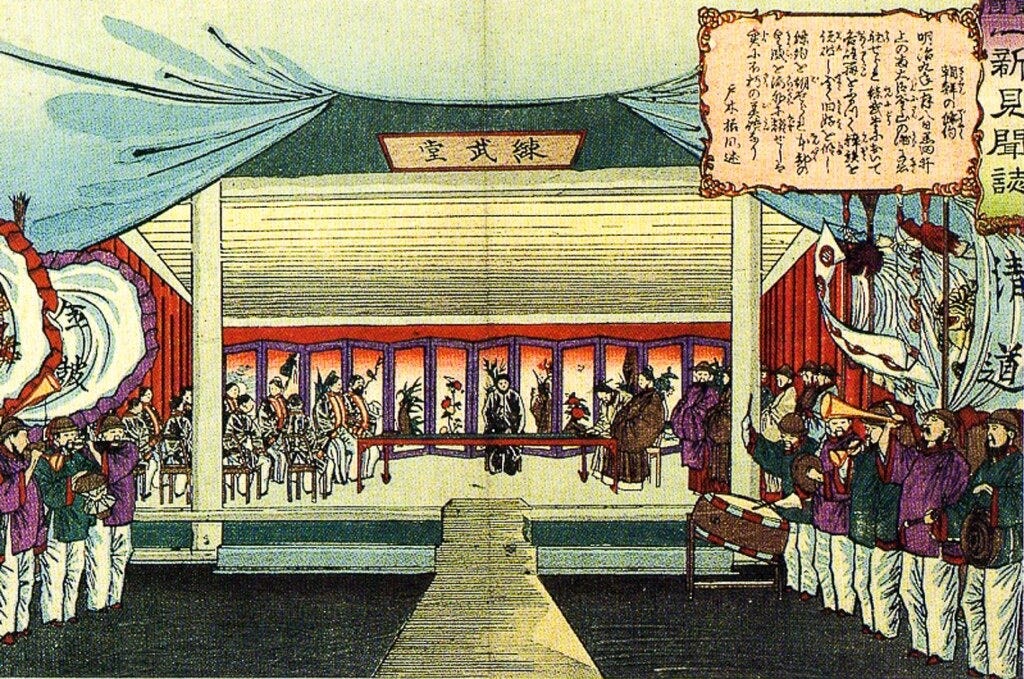

As it modernized, Japan forced Korea to sign the Treaty of Kanghwa in 1876, opening three ports for trade. This treaty created nearly the same "treaty port" system in Korea that the United States had imposed on Japan. Japanese merchants quickly took advantage of the situation to begin exporting to Korea - often re-exporting what they had imported from the United States and others through the system created by Japan’s own unequal treaties, and importing commodities such as rice cheaply from Korea. This created a strong and growing trade relationship.

Why would Japan treat Korea in the same imperialist way that it had itself been treated? There are a number of reasons and these Korea before 1876 had traded as an equal with Japan, but had a very close relationship with China, which provided it with defense and political and economic advice and acted as a trading partner. This was part of a much-debated calculus within the Japanese government. Some of the emperor's advisors wanted to invade Korea to give Japan's idle samurai something to do. They were hoping to create an empire, and to prevent violence by disaffected samurai at home. Others, though, felt that colonizing Korea was not at all appropriate. This debate had important political effects for most of the twentieth century.

To escape its own unequal treaty problem, Japan was willing to try nearly anything. It promulgated a constitution in 1883 to show Western nations how modern it was. The government subsidized industry to create a modern economy, and to support a modern military to impress Western powers. It even built a Western-style building known as the "Rokumeikan" (Deer Cry Pavilion). This was designed specifically to hold entertainments and Western-style balls for European and American diplomats. All this was done in the hope of convincing the Western Powers to revise the unequal treaties. Forcing unequal treaties on Korea was a part of this effort. Western colonial powers were more likely to respect Japan if Japan were also a colonial power.

The signing of unequal treaties in 1876 was only the fateful first step. A much bigger one would be taken in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. Then Korea would come completely under Japanese control after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. However, as the proverb goes, "a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step." In the case of Japan's empire, this was that step.

Beasley, W. G. Japanese Imperialism 1894 - 1945. 15. print. Clarendon Paperbacks. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010.

———. The Meiji Restoration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2019.

———. The Rise of Modern Japan. 2. ed. New York: St. Martin’s Pr, 1995.

Craig, Albert M., and Albert Morton Craig. Chôshû in the Meiji Restoration. Studies of Modern Japan. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2000.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Third international edition. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Thanks for breaking down a complicated history. It reminds me of how piss-poor Arab-Israeli relations started with British influence on both sides. Colonialism begets colonialism. Thanks for today’s lesson, Sensei!