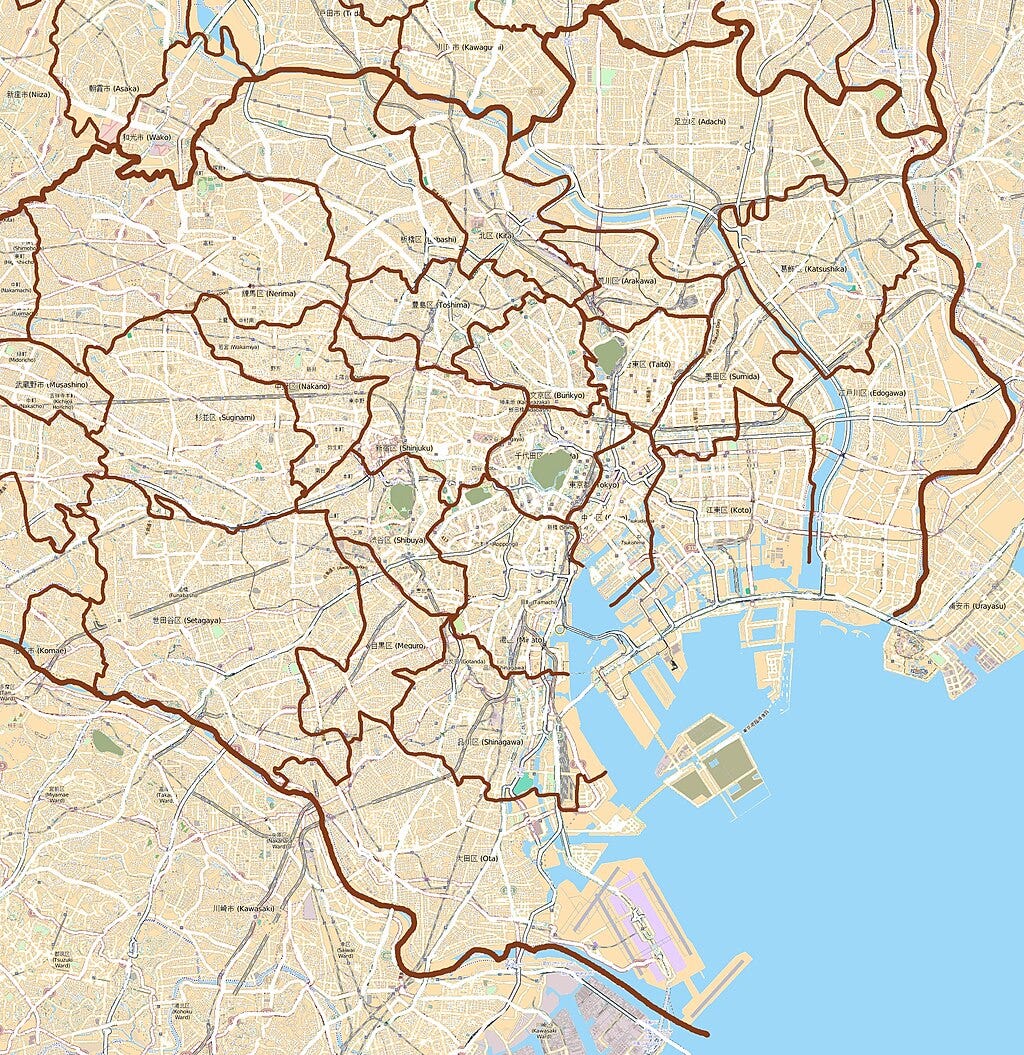

I “grew up” in Tokyo. No, I am not a Tokyo native. No, I am not even Japanese. So I’m not laying claim to any special knowledge or status. Its just that my formative years as a young adult I experienced in Tokyo. I am always surprised when I hear people, whether from Japan or outside of it, tell me that Tokyo is not “real Japan.” What they mean, I think, is that Tokyo is a world city. Greater Tokyo has a population of around 37 million. It is very modern in many ways. In Tokyo you can get food from nearly anywhere. You can always find people who speak your language, no matter what your language is. People seem modern and sophisticated. There are musical theater, movies, discos and clubs. Trains run on time. Some of the most cutting-edge sights in the world - such as 3-D screens on large buildings - greet you wherever you go. The Omotesando area is home to one of the greatest collections of modern architecture in the world. Tokyo museums display artworks and cultural treasures from all times and places. Tokyo seems to represent not Japan, but the modern world. “Real” Japan is the countryside.

Anyone who has lived in Tokyo for more than a couple of years will tell you that view is superficial at best. Tokyo is not really a megacity. It is a collection of villages. People born and raised in Tokyo are often known as “Edokko.” This just means children of Edo, the name of the city during the Tokugawa Period. Some argue that true edokko can only be people born within the original limits of that Tokugawa era city. Each town, known today as “ku” has its own history. Each has its place in the history of the city. Each its own famous residents and traditions. A line in the song "Bōhatei de mita keshiki" (The view from the breakwater) by Okinawan band BEGIN captures this sense. “According to the bartender," the song goes, "people born in Tokyo are actually small town people, too.” Tokyo is full of traditions. While it constantly reinvents itself, it also holds tight to its past and its history. For nearly 150 years, Tokyo has been the Capital of Japan. It is as real as Japan gets. Perhaps it is better to see Tokyo as having, like every other location in Japan a flavor and a character all its own. To see this, one has to engage in a kind of ethnography. That has always been, difficult in Tokyo, with all its great diversity. Like an ethnographer, one has to dig into not only the history, but the local society of today. The only way to do that is to ask the locals.

This kind of ethnography has been popular in Japan since before Taishō. Cultural Ethnography of Japan by Japanese is not unusual. According to Andrew Gordon, one of the critical questions for Japanese, during the Meiji Period was what it meant to be Japanese. Mark McNally and Tetsuo Najita have written about Tokugawa era attempst to answer this question. Not surprisingly, it's importance increased as Japan modernized. In a sense, Meiji was a time of action - modernization - and Greater Taishō a time of reaction. The questions for many intellectuals in Taishō included “what have we done?” A close second was “what have we lost?” Finally, the big one: “can we find it again?” The sense of lost identity became heavier as modernization continued.

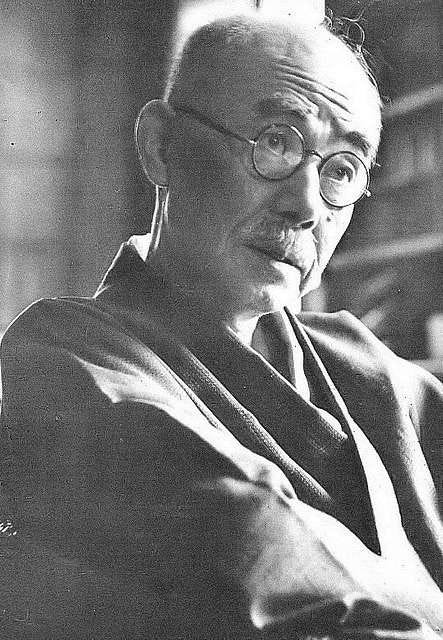

Yanagita Kunio

Folklorist and erstwhile ethnographer Yanagita Kunio attempted to answer these questions. His method was to seek out “real Japanese” in the countryside. He seems to have hoped to find Japanese who had not been touched by modernity. Then by collecting their stories and folk beliefs he tried to find out the answer to the questions above. He attempted to create an ethnography of Japanese village life in his 1910 book Tales of Tōnō. To get the stories he included in the book, he travelled to the Tōnō region of Japan. Once off the train, he had to rent a hose and travel the mountain trails. He visited widely separated mountain villages and isolated homes to collect his stories. The language in Tōnō was so different from his own standard Japanese that he had to hire an interpreter.

The book was a bestseller. It fed a public desire for answers to the same questions. High book sales launched Yanagita on a public career. He in turn lit a fire under the intellectual movement characterized by his search for a Japanese essence. Yanagita claimed that this project was important because rapid modernization had led to a general forgetfulness of Japanese identity and culture. Yanagita’s critique of his primary informant as “not a good storyteller,” seems to fit in with his goal. He said in his introduction that the man was an unsophisticated local villager. He claimed that he translated the stories for Yanagita without changing them. The first time I read this, I got the feeling that Yanagita was saying that a good storyteller, not being from the area, would not recognize the local cultural aspects of the stories. But a real, unsophisticated storyteller would. This was based on the idea that Tōnō people naturally understand their drama without enhancement. They were thus pure and untouched by Modernity in Yanagita’s mind. Yanagita’s claims that the legitimacy of this exercise extended to his choice of the village of Tōnō are also indicative of his search for cultural ‘purity.’

Yanagita was interested in Tōnō because it was so isolated, but near the cities and modern transportation systems of Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa-era Japan. Even in the modern world of Meiji, Tōnō provided a little haven of traditional Japanese culture. Yanagita mined this to find what had been lost in the modernization process. This attempt to find the exotic Japanese past reveals a kind of nostalgia. Yanagita and other intellectuals yearned for the Tokugawa period. Through the stories in his book, Yanagita passed on to modern Japanese the fantastic, ghostly beliefs of Tokugawa villagers. He provided Japan with a kind of mystical, mythical, exotic but not foreign past. One might even say that Ghibli stories like Spirited Away, (Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi) and Princess Mononoke (Mononoke hime) take part in this tradition. They are, however indirectly, related to Yanagita's folklore discoveries. Yanagita’s project was to uncover the tradition of Japan to domesticate the modernization process that was going on around him.

As I watch Princess Mononoke today, this double process of domestication always strikes me. The story is about modernization, industrialization, and the human domestication of the natural (and legendary) world. But the telling of the story makes that process of ambiguous value at best, and is often critical of it. In a similar way, Yanagita was trying to uncover an undomesticated, unmodernized Japanese past, in order to control at least the understanding of modernization and bend it to the preservation of Japanese culture. I am also always reminded of the achievements of Japanologist Ernest Fenellosa (1853-1908). An American, Fenellosa had a deep interest in Japanese and Chinese art. His teaching helped revive their study and preservation in Japan during the Meiji and Taishō Periods. Like Fenellosa, Yanagita seems to have wanted to preserve the Japanese past. He also wanted to make sure that past was always in the minds of people in Japan’s present. If Tōnō could be defined as authentic Japan, then industrialization and modernization could be thought of as nothing more than a layer on top of Japanese tradition. Japanese identity would not be fundamentally changed by modernization, only augmented.

The works of Yanagita, resonated with the concerns of the Japan Romantic School of novelists. It paralleled and supported the beliefs of the New Poetry Society of Yosano Tekkanand his wife Yosano Akiko. Their interest was in preserving Japan’s cultural heritage into modernity. Other novelists, poets, artists and cultural critics had similar inclinations. Natsume Sōseki, Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, Noguchi Ujō, and Nakayama Shimpei, all thought about what it meant to be Japanese. They tried to define and preserve that identity. During Taishō literary and cultural producers located “true” Japanese culture and identity not in the experience of the modernizing urban centers, but in a romanticized vision of the countryside, which they borrowed from as they tried to explore the relation of this ‘tradition’ to modernity.

Doak, Kevin Michael. Dreams of Difference : The Japan Romantic School and the Crisis of Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terrence Ranger, eds. The Invention of Tradition. Reprint. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Ivy, Marilyn. Discourses of the Vanishing : Modernity, Phantasm, Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Koschmann, J.Victor, Keib Oiwa, Shinji Yamashita, and Kunio Yanagita. International Perspectives on Yanagita Kunio and Japanese Folklore Studies Cornell University East Asia Papers. Ithaca, N.Y: China-Japan Program, Cornell University, 1985.

McNally, Mark. Proving the Way: Conflict and Practice in the History of Japanese Nativism. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Asia Center, 2005.

Nakayama, Urō. Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku/Nenpu. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980.

Patterson, Patrick M. Music and Words: Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952. New Studies of Modern Japan. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2019.

Silverberg, Miriam Rom. Erotic Grotesque Nonsense : The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times Asia Pacific Modern. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Tanizaki, Jun’ichiro. In Praise of Shadows. Reprint. Sedgwick, ME: Leete’s Island Books, 1933.

Yanagita, Kunio. About Our Ancestors: The Japanese Family System. Translated by Fanny Hagin-Meyer and Ishiwara Yasuyo Classics of Modern Japanese Thought and Literature. Reprint. New York: Greenwood Press, 1970.

———. The Legends of Tono Japan Foundation Translation Series. Tokyo: Japan Foundation, 1975.

Yano, Christine R. “Defining the Modern Nation in Japanese Popular Song, 1914-1932.” In Japan’s Competing Modernities: Issues in Culture and Democracy, 1900-1930, edited by Sharon Minichiello. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998.

Great post! I could easily see this expanding into a book. Perhaps something on Greater Taisho? It seems like a complex and interesting era.

I had an epiphany while reading this post. My family on both sides came to Hawai'i during the Greater Taisho. They came from HIroshima (Choshu) and Kumamoto (Satsuma), and though not as pastoral as Yanagita's Tono, the places they, and many Japanese immigrants to Hawai'i, were from were far from "modern" Tokyo of even the Greater Raisho. Places which may have been closer to the "soul" of Japan. Maybe we preserved some of this "soul" in Hawai'i with our bumpkinish osechi ryori feasts ladled from huge pots (not the pretty little compartmented boxes today's Japan enjoys) or the mustaches we sport like our great-grandfathers. I've always referred to Japanese American Hawai'i as a "perverse Taisho Snow Globe" because the only Japan most of us knew was through our ancestral lens. The values passed down from our great-grandparents were the strict and conservative rules of yokels. We all had this view of Japan as being full of pretty and not-so-pretty girls who won't kiss on a first date, because that's the way we were taught to be. I'm beginning to meet Japanese scholars of Japanese Hawai'i and they are fascinated by our food and behavior. I feel like Yanagita, trying to capture something win fiction we've lost , in a time before social media killed everything quaint and charming. Thanks for the post; I feel less lonely aout what I write now!