The name of the Taishō Period comes from the reign name of its emperor. That's the simple answer. Crown Prince Yoshihito became emperor in 1912 and took the reign name Taishō (大正), meaning “great righteousness.” This was a reference to China’s Spring and Autumn Annals.1 It was intended to convey good luck and a good image on the new emperor and his reign. Yoshihito was thereafter known as Emperor Taishō: the personification of his time. He reigned until 1926. A short 14 years. Short, but important, and oh so busy.

Taishō is not just the name of the period in which an emperor reigned, though. Why do historians attach such importance to it? As usual, there is more to it than that. In fact, historians of Japan prefer to talk about a “Greater Taishō” era from 1900-1930.2 This dating is not about Taishō as a set of years defined by an emperor’s period of rule. Something about the events, ideas, social changes, economic changes, and culture of the Taishō Period seems to be internally consistent. Taishō feels different from other historical eras. Taishō events correspond to Taishō attitudes. Taishō attitudes correspond to Taishō politics. That all fits in with Taishō culture. Which is all, really, why I am writing this newsletter, and starting with the emperor.

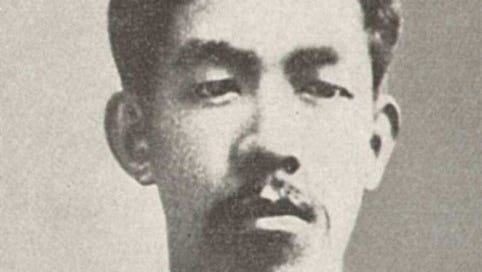

Born in 1879, Yoshihito started out with big shoes to fill, both publicly and privately. By all accounts, Emperor Meiji (r. 1868-1912), his father, was difficult to please. Emperor Meiji possessed larger-than-life status. He was the emperor in whose name Japan was “restored” to imperial rule after 268 years of government by the Tokugawa Shōguns. Whatever the realities of power at the top of Japan’s government, Meiji had reigned over political and social change the equal of any revolution. He bestowed the Charter Oath, recognizing the importance of the Japanese People to the Nation. He oversaw, even if only from a distance, Japan’s industrialization. He was there at the beginning of its imperial expansion. His reign was capped off with military victories in 1895 over China, a longtime cultural and political mentor of Japan, and in 1905 over Russia, one of the Western “Great Powers.” To say the least, Meiji was an imposing figure. He was, maybe, not the kind of guy you’d want for a dad. Even his grandson was intimidated by him. How do you follow an imperial act like that?

Emperor Taishō had a tough time with that. He was not of robust health. He wasn’t the dashing, intelligent prince on a white horse that his own son, Hirohito, would become. Instead, frequently ill, he contracted meningitis as a child. Although he recovered at the time, the disease appears to have come back to haunt him in adulthood. He was not intellectually gifted, either. He attended Gakushuin, the peers school for Japan’s elite, where he did not do well. While there, though, he rubbed elbows with a growing international group of students. Along with the Japanese elite, his class included two students sent by King Kalākaua of Hawaii.3 He must have bumped into students from other Asian nations as well. Students from Asia were going to Japan to get the most modern education in Asia. Whether he was aware of the growing connections between the nations of the world that these schoolmates represented, the fact is that a new globalization was to be a part of the era he would preside over as emperor.

In many ways, Taishō seems to have been a very “in-between” emperor. He was in between Japan’s first “modern” emperor, the great Meiji, who bestowed a new constitution upon his people, and Japan’s longest-serving emperor, Shōwa, in whose name Japan fought a nearly-suicidal war and then adopted a peace constitution it its wake. Yet Taishō’s reign was a key part of Japan’s modern history. In Taishō, Japan joined the world. Still, Emperor Taishō was not what we might call a “great man.” One of his nicknames was “manifest deity.” an ironic play on the power of the United States and the Japanese idea that their emperor was in fact divine. Needless to say, there is little sense of greatness here.4

Taishō has a reputation for mental illness. This may or may not be true, but he wasn’t mad. He suffered from poor health. He was an inveterate drinker, and misbehaved. He was a womanizer. He was eccentric. His very human behavior in a very public position led to problems. Then, in 1919, he began to have a series of strokes. The stress of his position and public appearances seemed to be too much. The Imperial Family Council and the Privy Council felt he should no longer appear in public. His son Hirohito became regent. He took over all imperial duties while Emperor Taishō “recovered” in solitude outside of Tokyo.

This is the man who gave the Taishō Period its name. In many ways he was representative of the character of the era as well. His own apparent unreadiness to assume the throne reflected the shock most Japanese felt at the death of Meiji. Millions mourned publicly. General Nogi Maresuke, a famed commander in the Russo-Japanese war, committed seppuku (ritual suicide), as expected of a samurai, following his lord into death. Famed author Natsume Sōseki described the feeling all over Japan as a sense of ending. Sōseki's character in the novel Kokoro explains that the growing greatness of Japan in the Meiji Period was identified with Emperor Meiji. Japanese felt a pervasive sense of loss.

In truth, though, the spirit of the Taishō era can be found as early as 1900. By that time, Japan began to change direction after its jarring Meiji reforms. During “Greater Taishō” Japan leaned into an ever-more connected world. Through trade and political and cultural exchange Japan joined the so-called Great Powers. It also conquered Taiwan and Korea, becoming an empire like many of them. It created astonishing new technologies and industries. Japanese ideas, art, and modern literature impressed the world. Taishō saw expansion of the Japanese People’s participation in politics and culture. Japan helped shape the global music industry, and developed literary, intellectual, and artistic cultures that are still alive today.

In Taishō, the Japanese came to see themselves as part of Asia. In Taishō they saw themselves as able to have opinions about Japan and about the world. Taishō can’t be defined by its emperor. It can’t be defined by its politics. Those lenses are too narrow. This 30-year period from 1900-1930 must be understood as a series of interrelated changes to all aspects of Japanese society. That’s where this blog is going.

Thanks for reading. I’ll start next week by looking at Taishō Democracy. That will form the foundation for other explorations. During this journey, I plan to look into art, culture, performers, personalities and ideas throughout Taishō. If it works out, maybe I'll go beyond that. I hope it will be an interesting ride.

Sources I consulted for this post:

Bix, Herbert P. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Nachdr. New York: Perennial, 2002.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Third international edition. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Minichiello, Sharon, ed. Japan’s Competing Modernities: Issues in Culture and Democracy, 1900 - 1930. Repr. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

———. Retreat from Reform: Patterns of Political Behavior in Interwar Japan. 2. print. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawaii Press, 1986.

Oda, Yasunori. Nihon kindaishi no tanken (Exploration of Modern Japanese History). 1st ed. 1 vols. Kyoto: Sekaishiso Seminar, 1993.

Ota, Masao. Zōhō Taishō Demokurashii Kenkyū (Supplementary Taishō Democracy Research). Tokyo: Shinsensha Co., Ltd., 1990.

Pyle, Kenneth B. The Making of Modern Japan. 2. ed. Lexington, Mass.: Heath and Comp, 1996.

Minichiello, Japan’s Competing Modernities. p. 2-3.

ibid.

ibid. p.3.

ibid. p.6.

These posts have been great! They have possibly inspired a new novel set during the period in Honolulu with a character loosely based on two real-life policemen:Hans Kashiwabara and the brother of Steere Noda (his name escapes me). The narrative would take stylistic cues from Dashiell Hammett. Keep the posts coming!

Wow!: "In Taishō they saw themselves as able to have opinions about Japan and about the world. Taishō can’t be defined by its emperor. It can’t be defined by its politics."

Such a powerful article. Thank you Dr. Patterson! I am looking forward to reading more about the Taishō Democracy and art!