In 1889, Kuroiwa Ruikō published Muzan 無惨 (In Cold Blood), his first original story. Because it is Meiji, rather than Taishō, I am a little hesitant to put it in here. However, binary thinking about historical periodization is not my style. I think that Emerson was right when he noted that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Not that I am claiming to have a big mind. There’s that inconsistency again. Anyway -there is, of course, some debate in literary and historical circles - as there always is - but we can classify Kuroiwa as being, if not the first, then at least one of the first Japanese to publish an original mystery story.

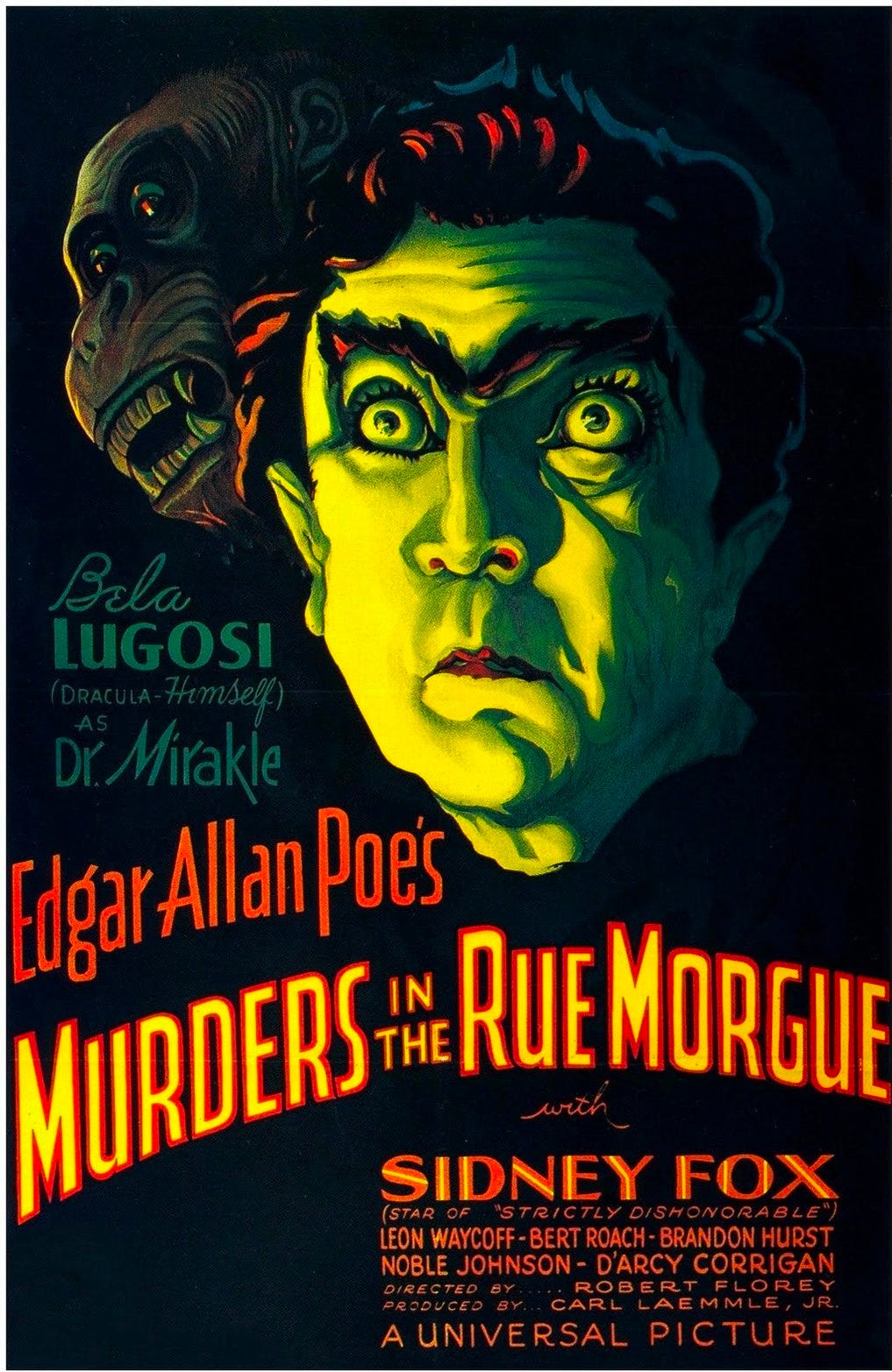

Muzan begins with an unidentifiable corpse washed up on the bank of a river. The corpse has numerous wounds, which Kuroiwa went to some trouble to describe in gory detail. Then he begins with questions - where could this corpse have come from? Where and how did it get into the river? Why so many wounds? He talks about the headlines in the newspapers, and likens the case to Poe’s Murders on the Rue Morgue. It’s a pretty riveting read. Unfortunately, like Yosano Akiko, to whose group of literary lights Kuroiwa was adjacent, but probably a bit too pedestrian to really join, I can find no evidence that Muzan or any of his other stories have ever been translated into English.

Kuroiwa was not prolific, but he was personally very deeply interested in mysteries, and published Japanese translations of American mysteries as well. Muzan was his original work. He prefaced it by calling it a “new story idea,” that “has no luster and no flavor, no plot, and is without any waves or winds.” I take this to mean that it lacks the ups and downs of what he refers to later in the preface as an art novel. He goes on to say that his novel is from the point of view of someone who likes art novels, is nothing but a factual article based on logic. However, he says, if you look at it from the point of view of logic, it is very much an art novel. This contradiction made me think of some of the things I have heard from friends who are devotees of the noir genre: the monotone voice of the narrator; the matter-of-fact depiction of horrific events and the depravity of human nature. I am no literary critic, and I am not claiming Kuroiwa was thinking or writing about noir in Japan of 1889. His words just resonate with what my favorite noirist (is that a word?) Scott Kikkawa (on Substack as Honolulu Blotter @scottkikkawa) has told me about the nature and attitude of noir.

I'm also working from the knowledge that Japan is one of the world's noir centers - noir is insanely popular there, with excellent contemporary writers producing some of the most interesting, and disturbing, noir available today, some even in translation (Natsuo Kirino's Real World is one excellent example). That interest in noir is not limited to novels - the manga and anime recently reproduced in live action on Netflix, Cowboy Bebop, is as much a noir as it is science fiction (It is also a Western, in the same way that Joss Whedon's Firefly is a Western).

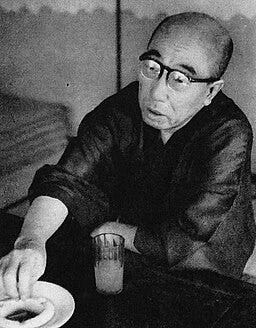

Kuroiwa was not alone in referencing Poe, either. Poe has had a long run of love from the Japanese. Poe inspired Kuroiwa. He also inspired Hirai Tarō (1894-1965) to the extent that Hirai became one of the most prolific, and still famous, mystery authors in Japanese history under the nom de plume Edogawa Ranpō, which is a wordplay homophone for Edgar Allan Poe (say it fast three times). He was the first Japanese author I learned of - even before Natsume Sōseki.

All of this is to say that Japan is a paradise for mystery lovers. Every subgenre of mysteries can be found there (more English translations for the world please), and that has been the case since even before Taishō. Japanese read. They read often, and in great quantities. That is still true, though less so, even in the age of the smartphone. In fact, in an interesting confluence of literacy and technology, the first-ever novel in the world typed entirely on a cellular phone (keitai shōsetsu- cell phone novel), called Deep Love was published in Japan in 2003 by an author named Yoshi. Since then, keitai shōsetsu have become a genre of their own. As I mentioned in an earlier post on novelist Shimada Seijirō, this reading culture was what got me to learn Japanese. I could not walk past all of those bookstores in Japan - in the 1980s they were everywhere - without knowing what was in those books. The generally small English language collections probably also played a role. I wanted more, and the only way to get it was to learn to read. What a treasury I found!

So back to Meiji-Taishō. In this period, and I think particularly in Taishō, authors, poets, journalists - writers of any type - were everywhere. They usually did not make a lot of money. However, many, like Yosano Akiko, Edogawa Ranpō, and Kuroiwa Ruikō did make a name. Their exploits about town were not only fodder for what we would call tabloids. They were so famous, and their intellectual influence was often such, that they could make or break the cafes, bars, and businesses - even entire entertainment districts - that they frequented. Some wrote about what they did and where they went, and those diaries became tour guides to an extent. Nagai Kafū’s subject was his city – Tokyo. Natsume Sōseki's book Botchan is really nothing if not a diary of a young student's life in Tokyo, and all the places he went and the things he did, interspersed with personal family, finance, love, and friendship issues that move the story forward. It is a wonderful read. Meiji and Taishō were a time when the lives of writers impacted the lives of nearly everyone else in Japan. The antiquarian in me, and the luddite who lives in my brain, romanticizes this period, even while the historian who owns my conscious mind reminds me that things in the past weren't "better" than they are today. Still, I long for Taishō, in large part, thanks to these writers, and to the composers, musicians, movie producers, actors and comedians that made up the greater popular culture scene.

I hope, on a future trip to Japan, to find some copies of Kuroiwa’s Yorozu Chōhō newspaper where I might be able to unearth some original print versions of Muzan and other Kuroiwa stories. Maybe I can find out, too, if there are English language translations languishing from the early 20th century. If not, I am not a great translator, but I know someone who is. Maybe I can convince them to take a risk on a mystery writer from Japan’s past.

This is a post that really spoke to me! Poe may be considered the grandfather of noir in its proto form, as his Murders in the Rue Morgue featured murder as a centerpiece of a narrative and took a clinical view of the act. Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle heavily influenced Japanese writers (and some would argue continue to do so). Raymond Chandler admired Dashiell Hammett for his "unsentimental" approach to murder, and clearly we see in your short synopsis of Kuroiwa's Muzan that the pondering of the corpse lacks the sentimentality thatg make up other sub-genres of mystery. It sounds hardboiled. it sounds procedural. It sounds noir. I think it's no accident that Japan and France, two noir-loving countries, are also two nations with impeccable style. America has turned its back on noir: I've been told by many a literary agent that "noir does not sell". It's not surprising. It's too stylish, too cerebral. It's too bad. America gave birth to noir, and we, too were once a stylish country. I think when we descend into the cheap and the disposable, we lose our appreciation for more subtle forms of expression. Japan, as you said, and France, still read. We just stream videos. It's no wonder we went from the best-dressed place in the world to wearing sweatpants and dri-fit t-shirts everywhere. You have neen astutely pointing out that Taisho was a time of transition, and I think that a society in transition is one of the ingredients for noir: postwar America, Frsance in its Fourth and Fifth Republics, pre-statehood Hawai'i. Disillusionment comes from not keeping up with the times or moving too fast for them, and anyone who says they're coping at the right sped is living in denial. Well played, Sensei!