Hats

An ode to Taishō fashion

I love hats. I only own a couple, mostly because the realities of the modern world (read: the low ceiling of my car) combines with a self-conscious sense that no one else around me is wearing them. I suppose I should qualify my love of hats. I am not a baseball cap fan. Even less a backwards baseball cap man. That is not a value judgment. It comes from the context of growing up in the late twentieth century. Among the late 70s fashion rules that has ossified in my head is the idea that one should never wear a baseball cap backward. It makes perfect sense that a rule so hard and fast would be one of the first ones broken by fashion forward men in the 1980s. After all, what is fashion if not a way to rebel against the choices of the previous generation? Hats, like fashion, make a statement.

Japan has a long history of making statements with hats. Shōtoku Taishi (Prince Shotoku) is said to have established the Kanʻi Jūnikai ranking system based on Confucian ideals, and designated by hats, to classify imperial officials in in the between 574-622 CE. I absolutely love those hats. Every time I see an image of a capped confucian scholar, I burn with envy. No joke. Which brings me to Taishō era hats.

I think you can tell a lot about a culture from the hats worn by both men and women.

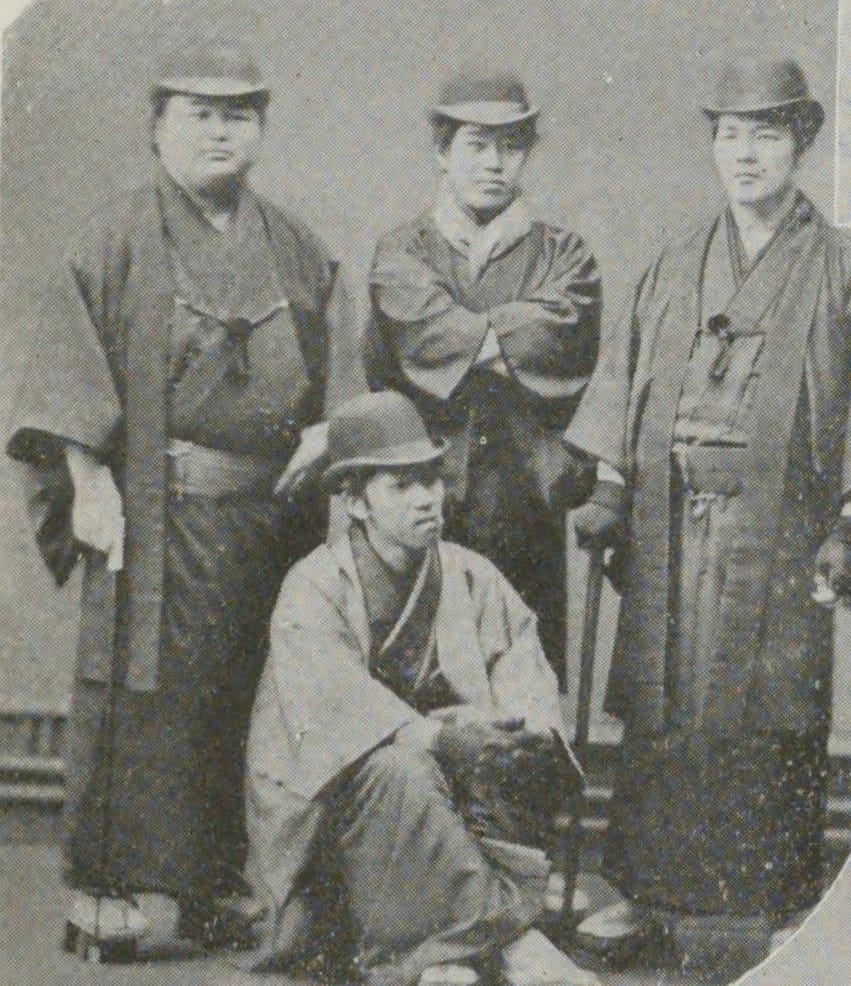

One of the key things I appreciate in the images above is the juxtaposition of Western style hats with Japanese clothing - specifically the kimono and geta (Japanese raised wooden clogs). Iʻve read many articles and chapters in which this juxtaposition is explained as a kind of cultural blending. Some authors have explained it as confusion in the process of adopting and adapting Western ideas during the early Meiji Period. I think thereʻs more to it than that. Personally, I really like this look, and so it probably shades my interpretation. Honestly, though, what shades my interpretation more is the novels and photographs I have encountered over many years studying and teaching Japanese history.

My dad was a bootstrapping businessman who lifted himself from poverty and provided a good middle class life for his family as a salesman, manager, and newspaper publisher in the mid-late twentieth century. He often told me “dress for success.” What he meant was that dressing like someone whom people could take seriously; like someone with self-confidence, can ultimately have a reflexive psychological effect. If you look like who you want to be, you can also feel like who you want to be. Wearing a nice suit can help you feel like a successful businessman. Even if, like me, you were a first-year-out-of-college advertising salesman for a declining local weekly newspaper. If you take yourself seriously, he said, others will too. Clothes show that. He was not wrong. So maybe some Japanese businessmen were wearing top hats because they hoped that would help them feel more like the Western businessmen that were, supposedly, the model for self-improvement in the Meiji and Taishō eras.

Still, my dad was not Japanese. The “dress for success” school of cultural blending in Taishō history is a bit weak as an explanatory model. As Western style business came to Japan, no doubt some Japanese thought to dress for success, and chose a mixture of Japanese and Western clothing as a way to suggest modernity, confidence, trustworthiness, and self-worth to others. I can buy in to that. To a certain degree. However, I donʻt really think that was the reason for the majority of men who did this, and I donʻt think many who did hope that adopting a top hat to channel Western business acumen would have tried it even a second time; or even necessarily bought into the idea that there was such a thing as “Western business acumen.” This interpretation just doesnʻt explain much.

Meiji and Taishō men and women made fashion choices, and those choices were not, I believe, a result of cultural confusion, but instead came from deliberate decisions about how they wanted to project their own image within their social and historical context. They werenʻt trying to impress Western people. They wanted a look they felt comfortable in that projected something about them. And really, they looked GOOD. Not confused.

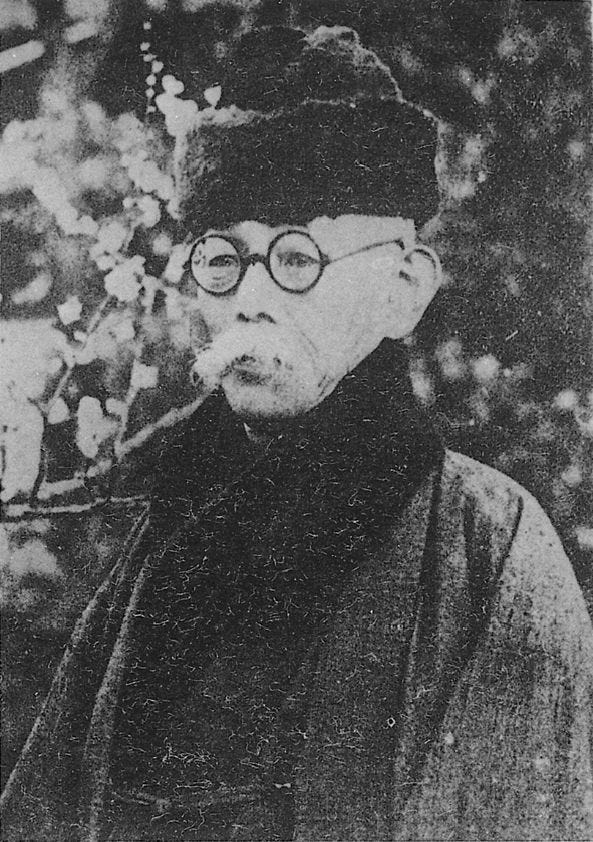

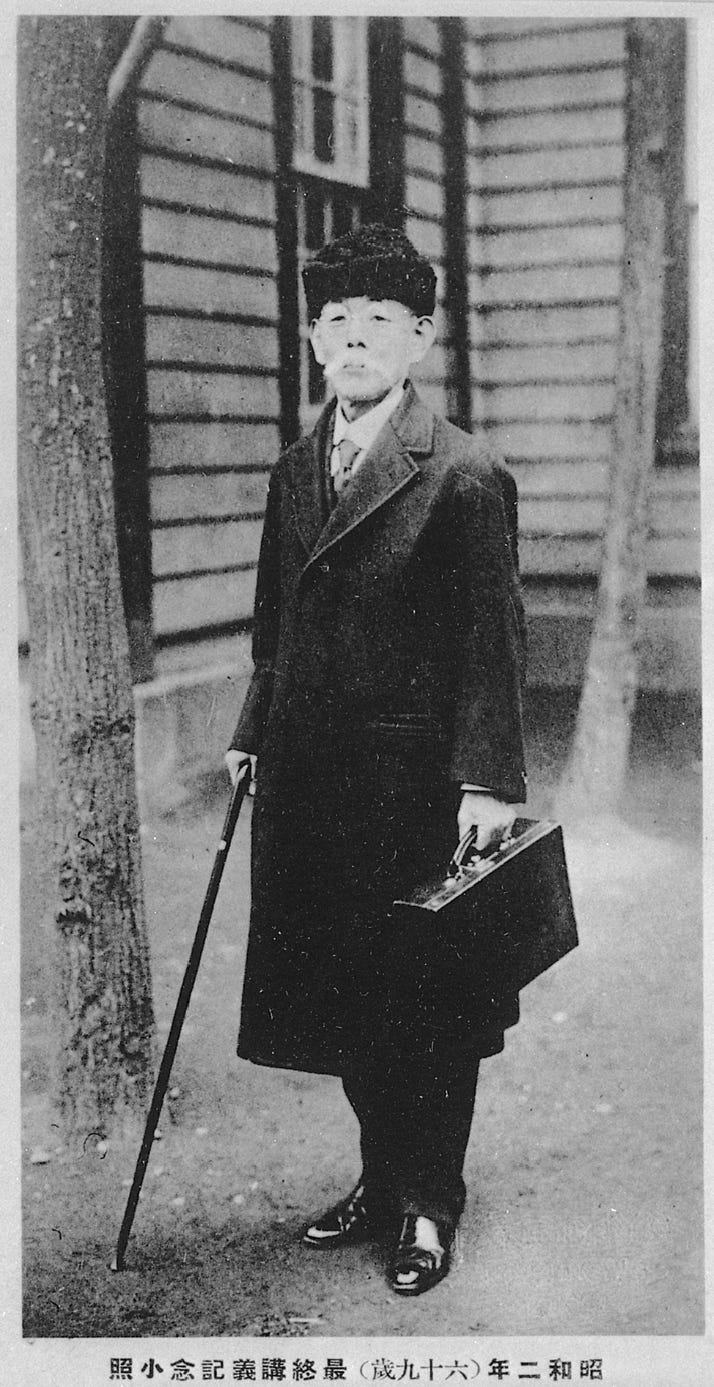

In the image above, literary light and Drama pioneer Tsubouchi Shōyō is wearing a very warm and really beautiful hat. It is not, obviously, Japanese in style. Heʻs wearing it with a kimono and a Japanese overcoat known as a haori. He also appears to have his neck protected by a scarf. This is a man with a put-together look that he has considered. It may be his daily go-to, though he dressed in more Western garb, as well. But heʻs clearly got a style. This is not a man confused about what to wear, how, or even whether, to look “Western.” Heʻs not trying to at all. If anything, he looks distinguished, authoritative, and approachable at the same time. He knows how to put together an ensemble. Its this kind of picture that leads me to think that cultural confusion over adopting, and how to adapt, Western fashion was less confusing than is often made out. Look at Tsubouchi when he wanted to wear a suit:

And the hat remains, the perfect topper for a cold morning. Such a wonderful hat. Hats, it turns out, were popular among men in Meiji and Taishō Japan. Mostly, I suspect, for the same reason they were popular at the same time in New York, and London, and other places all over the world. They keep your head warm, protect it from rain and snow, and they look good. This is especially true in the world of the 1920s, when everyone did not have a car, and walking, riding horses, or riding in open carriages or jinrikisha (“human-powered cars” that we in the West call, with characteristic linquistic brutality, “rikshaws”) was much more common than it would become as the mass manufacture of automobiles, and the lowering of their roofs for streamlining and to save money, all but made hats obsolete.

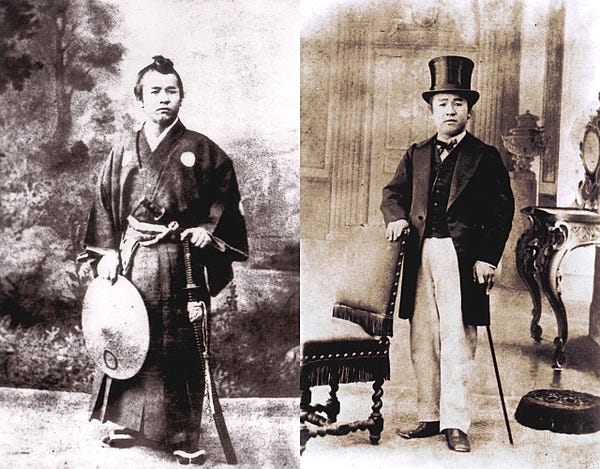

However, there was another reason for their popularity as head toppers for former samurai in the Meiji period, and though this reason did not last into Taishō, I find it fascinating all the same. In early Meiji (1868-1912), as the Japanese government changed from the Tokugawa Bakufu to the “Modern” restoration of the Meiji Emperor, the samurai lost their special status. Reduced to commoners, they were required to cut off their topknots (mage), which were symbols of their samurai status, as a sign that they were now the same as everyone else. Understandably, some were reluctant to let go of one of the key pieces of their identity - a haircut that involved shaving the pate, mostly because wearing a samurai helmet on top of a mass of hair was extremely hot and could contribute to heat stroke - something youʻd rather avoid when your life depends on being able to think through the next sword stroke in battle. When the helmet was off, the long hair in the back was groomed with oil, pulled forward into a braid, and laid on top of the bald part of the head. This style indicated samurai were warriors, and it told them and others about their status. After many generations, I understand why they would not want to give that up.

Those who were not ready to see their identity chopped off to fall on the ground at their feet often chose to conceal their transgression with a hat. Many chose top hats - especially businessmen.

Shibusawa Eiichi, wrote the book on being an industrialist in Japan. His top hat made him look every bit the part.

Others chose bowler hats, straw boaters, berets, billed caps, shapeless pate-toppers that looked like the rain had destroyed the brim so many times it was not worth maintaining any more. I love these “professor hats.” They say to the world: “Iʻve been outside in the rain and snow and heat in this hat.” They scream artist, or naturalist, or architect, or just leisure time hiker. Hats can tell us so much. And women played the topper game, too.

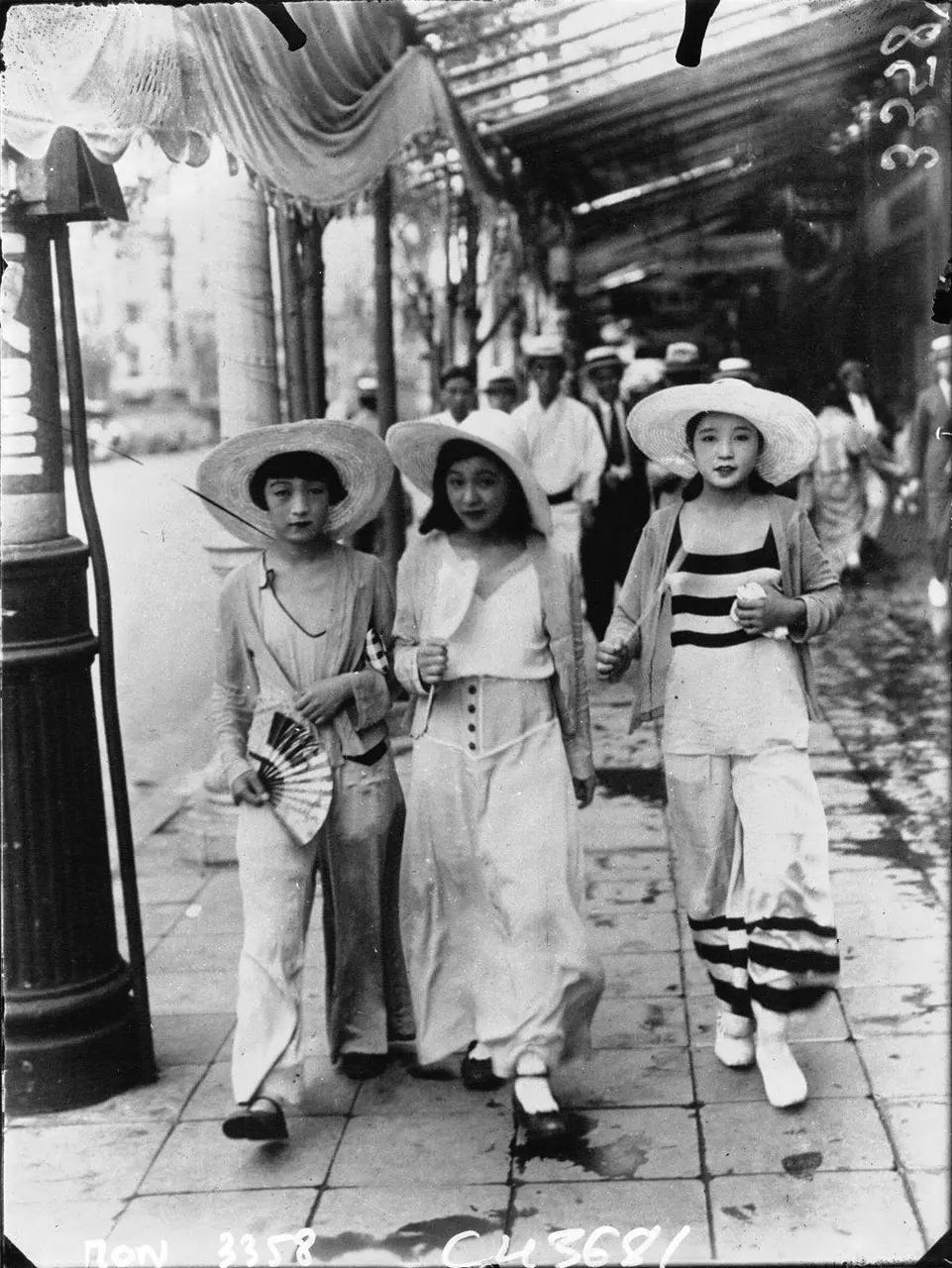

Their hats are glorious! They are so much more than just protection from the sun, or covering for delicate hair on a windy day! They are in both these pictures clearly a part of the entire aesthetic. The three girls above are scandalously dressed in casual beach wear while doing a Ginbura - cruising the main Ginza thoroughfares - todayʻs equivalent of dressing to the nines to walk and be seen on Ometsandō Avenue or Rodeo Drive in L.A.. The hats compliment the outrageous fashion statements being made - that these women can decide what they think looks good, that men and society can be scandalized, or accept whatʻs cool. That time is moving on. These are Modern Girls on a modern avenue in modern clothes complimented by the hats that set everything off.

But what I really love about this photo? Look in the background. Nearly all the men ogling the girls back there are also wearing hats. There are boaters and homburgs, dark bands and white bands. All on top of Western suits or yukata.

This is choice, not cultural confusion. They are wearing their clothes fashionably in a social situation, and the hats top it off. They are wonderful, and I wish we wore more hats today. Then I would not feel so alone in my woven summer borsalino, strolling through campus, trying to look something like a white Kikuchi Takeo.

I love this piece! I, too, mourn the passing of hat wearing and I’m trying to bring it back in my own way. I’m taking a vintage Mayser fedora in dark olive to Kyoto in a couple of weeks to wear along the Tetsugaku no Michi, where it should not look out of place. Your dad’s advice holds just as true today as when you heard it—it’s too bad practically nobody heeds it anymore in America. Great images in this post, but the last is the best of all—let’s go somewhere you can sport that lid, Sensei!

The other reason why I think people wore hats was the smoke and general air pollution. That's another reason why you take them off indoors because you don't want a hat with stinky ash on your head there.

As air pollution decreased in cities the wearing of hats did likewise. Out in the countryside where people wear hats for sun protection they are still worn because the sun still shines just as it did.