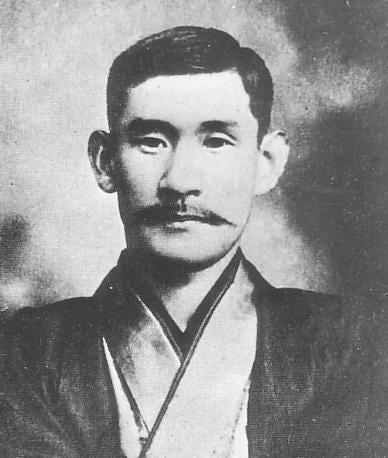

In one of his most well-known photographic portraits, Shimamura Hōgetsu (1871-1918) stares at the camera from his desk chair. Surrounded by books, the Waseda University professor of English Literature looks young but intense. His mustache is well-groomed, but not particularly symmetrical. He’s just slightly disheveled but charmingly clean-cut. His light-colored kimono and darker haori are draped perfectly. He has his right elbow on the desk next to him, and is sitting comfortably in swiveling desk chair. He radiates scholarly confidence. As this photo reveals, Shimamura was a writer who combined Western culture with Japanese traditions. His personal and professional goal was to use literature, particularly Western literature, to move Japanese society into the modern world. He was consumed by this mission.

Shimamura sat, as he did in the photo, casually in the center of a movement organized around his literary journal: Waseda Bungaku (The Waseda Literary Journal). Based on the Waseda University campus where Shimamura worked, this magazine provided Shimamura with the opportunity to gather and lead some of the greatest language artists of his time in his effort to get Japanese to change their ways and their thoughts. A better Japan, or at least a more modern one, through literature.

Shimamura played the field. He seemed to sense that despite a generalized respect for scholars, an academic elite was never going to have the mass effect on popular culture and society that he wanted. However, he recognized that if he could introduce the literary world of Japan to artists, socialites, musicians, actors, and playwrights, he might have a chance.

So along with his responsibilities as father of a young family and his commitment to Waseda University and to the literary journal, he became an impresario. He founded and ran The Geinō Kyokai (association of performing artists), within a physical theater space known as the Geijutsuza, which still exists today. He used this theater company to produce Japanese versions of Western plays and novels, as well as some Japanese works.

In the process he influenced writers important in Japan’s modern literature. Kitahara Hakushu spent time with Hōgetsu. Poet and song lyricist Noguchi Ujō was a former student. Shimazaki Tōson a colleague.

Hōgetsu applied to his dramatizations of Western works an early version of Herbert Loewy’s 1950s MAYA design principle formula - MAYA is an acronym that means “Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable.” Loewy formulated this after, like Shimamura, he realized that introducing the newest design, or the newest idea, to people without giving them something familiar to hold on to usually led to rejection. Hōgetsu used it for entertainment. He realized that Western and Russian plays, and even the idea of musical theater, were so full of cultural differences that if he presented them as-is to his Japanese audiences, they might have short-term novelty value, but they would never get and keep audiences. That would sabotage his efforts to use their contents to familiarize Japanese with modern ideas.

He chose subjects - among his earliest were the opera Carmen, and a musical version of Tolstoy’s The Resurrection, which he had seen while visiting England, in part because their emotional content tracked with the kind of dramatic tension Japanese audiences for Kabuki, for example, were already used to. Jilted lovers. Class differences. Unrequited love between people separated by duty, or social class, or both. He kept their Western settings, but dramatized them with Japanese elements in the costumes, makeup, staging, and music. This “cultural MAYA” was designed to make his audiences feel comfortable enough that they could think about the story and its message, rather than find themselves bewildered by the foreignness of everything.

Thus, as director of the Geijutsuza, Hōgetsu mentored composer Nakayama Shimpei. They had connections to the same hometown in Nagano, and Nakayama, who went to Tokyo to study music, was able to work as a servant for Shimamura when he was not in school. Shimamura recruited him very soon upon his arrival in Tokyo, recognizing the usefulness of an in-house composer for his musicals. Nakayama worked for room and board, and graduated in 1912 from the Japan School of Music. He then took part time work with Hōgetsu’s theater company. It was this connection that led him to become the composer of Japan’s first “popular song” - “Kachusha no uta” (Kachusha’s song, 1914).

Nakayama, under Hōgetsu’s mentorship, became one of several popular song composers in the ‘teens and ‘twenties, (1910-1929) who set the pattern for Japanese popular music in the first half of the twentieth century. Many of Nakayama’s practices are still used today in some popular music genres. Nakayama gave Shimamura credit for his MAYA-like strategy for making new popular songs palatable. Shimamura was not himself a songwriter. He did not teach Nakayama his craft. Instead, he taught him a way of thinking about creative innovation - a formula for making new culture that went beyond the music and into the collective consciousness of Japanese Society.

Through his duties at Waseda Bungaku, Hōgetsu’s literary magazine Nakayama met some of the brightest lights of the Taisho literary world, including some who would eventually become his lyricist collaborators: Noguchi Ujō, Kitahara Hakushu, and Soma Gyōfu. He thus became associated with this modernizing group of authors and artists at the moment when they were launching their modernist movements. Thanks to Hogetsu, Nakayama became a part of the process. Central, in fact. His role writing songs for the Geijutsuza made him the perfect person to set the authors’ poetry to music - to give them a popular culture outlet for their literary works. This allowed them all to make a little money (Gyōfu even wrote to Nakayama once thanking him for the commission and expressing interest in working together again) and to influence the broader culture while they were at it.

In many ways, then, Shimamura’s desire to modernize Japan through literature operated through Japan’s burgeoning market economy. Shimamura’s vision, which I have equated with Herbert Loewy’s much later-elaborated design concept of MAYA, was not explicitly capitalist. It was designed to maximize the distribution of cultural awareness. But it used private theater in order to accomplish this. Taishō was a time in which capitalism was often used not for personal gain, but for social good. That choice, and his desire to see Western culture spread not as a novelty, but as information, made him much more than an impresario. He was in so many ways an entrepreneur in the sense of Joseph Schumpeter’s definition of the word. Someone who sees a need, and is willing to change the market by offering a new product that challenges old modes of production. Today, we call this “creative destruction,” and it is a technology buzzword. Shimamura Hōgetsu was practicing creative cultural destruction in order to build back Japan’s strength and place in the world.

—---------------------

Patrick Patterson, Music and Words: Producing Popular Songs in Modern Japan, 1887-1952, New Studies in Modern Japan (Boston: Lexington Books, 2018, https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781498550352/Music-and-Words-Producing-Popular-Songs-in-Modern-Japan-1887%E2%80%931952.

Nakayama, Urō. "Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku " In Nakayama Shimpei Sakkyoku Mokuroku/Nenpu. Tokyo: Mame no Kisha, 1980.

Sonobe Saburo, Enka Kara Jazu E No Nihonshi (Shokosha, 1954). 358.

Showa Ryūkōkashi (Tokyo: Asahi Shimbunsha, n.d.).46.

“A writer who combined Western literature with Japanese tradition.” Sounds very familiar to me….

Unconsciously, I’ve been employing MAYA to sell Hawai’i literature and history to American readers outside Hawai’i by wrapping our Territorial home as it really was in hard boiled mystery.

Hogetsu is my new spirit animal!